Zeralda's Blackletter

How fonts can encourage complex emotion in children

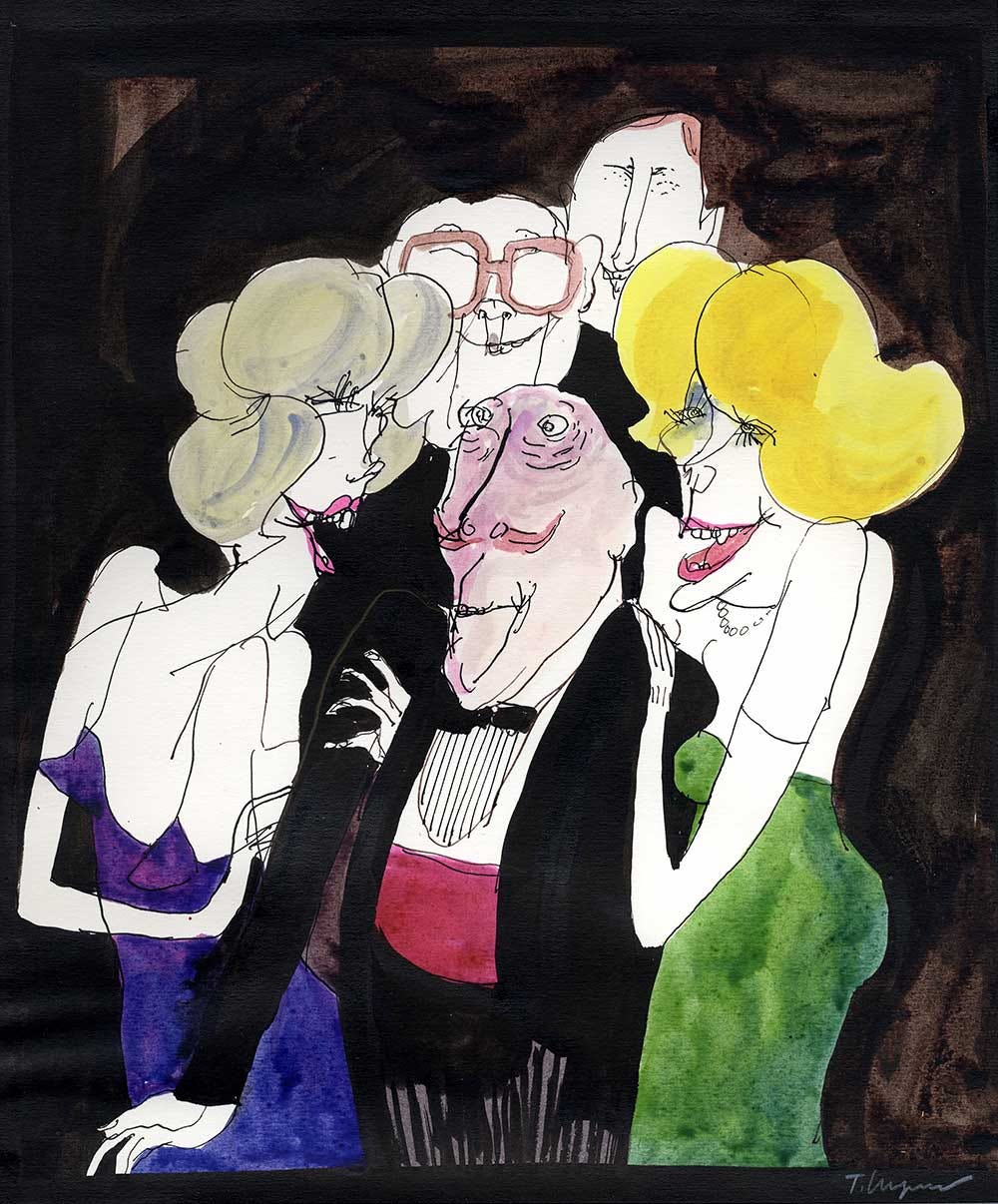

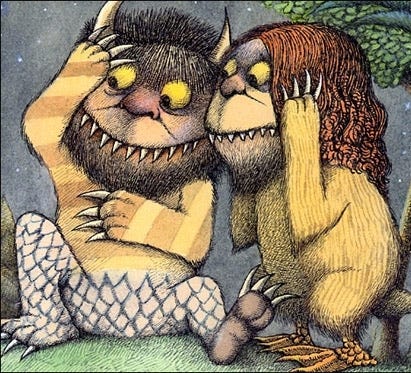

In Tomi Ungerer’s children’s books, villains have noses that look like old gym socks filled with jello. They are drooping, swollen sausages that resemble the penises he drew in erotic illustrations. Despite his art’s eccentricities - or perhaps because of them - Tomi Ungerer’s illustrations found countless homes. He produced advertisements for international airlines and alternative magazines, posters for jazz festivals and transgressive nightclubs, anti-war political satire, and piles of children’s books.

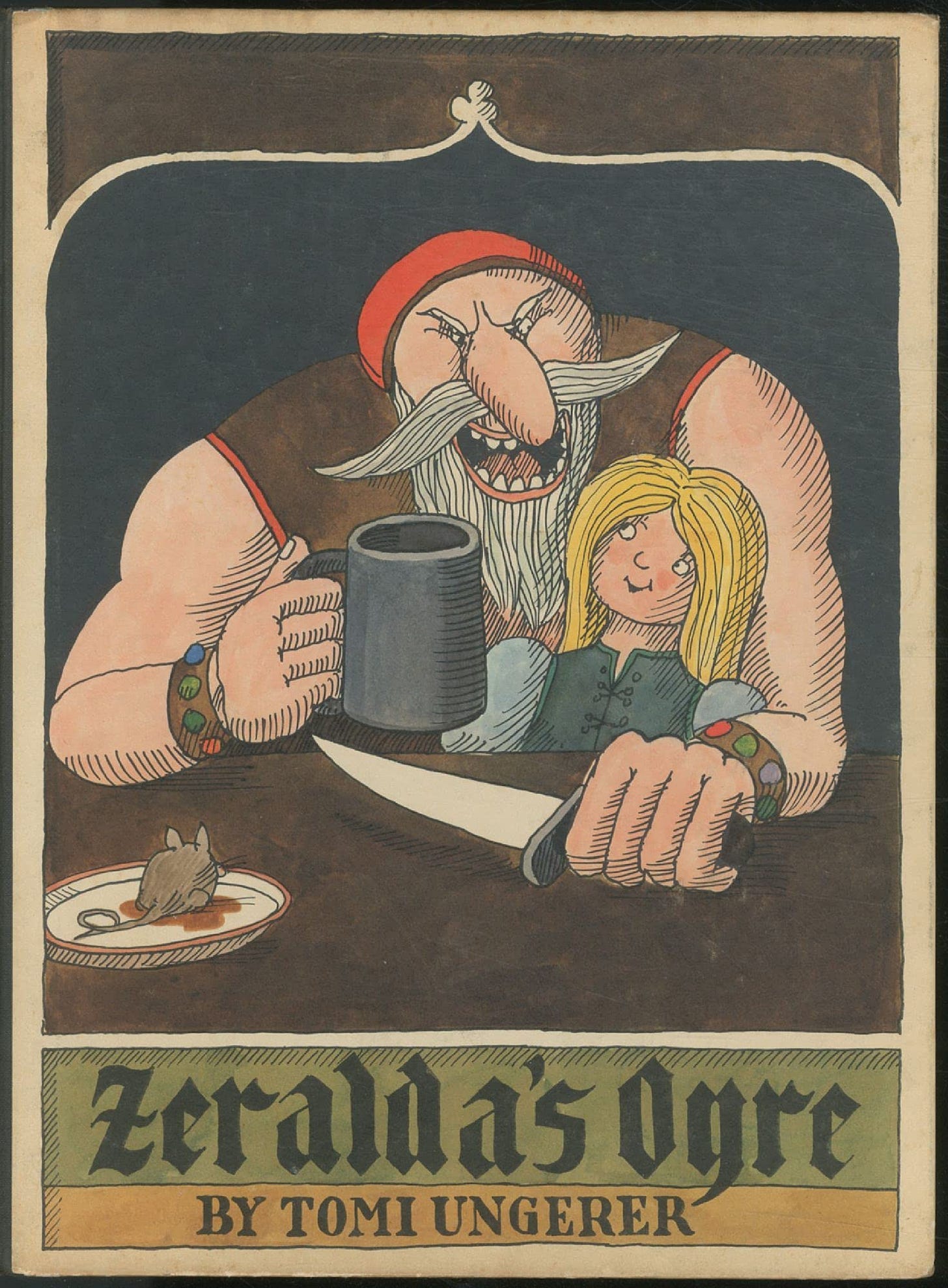

One of those children’s books was Zeralda’s Ogre, in which a child-eating ogre kidnaps a little girl, only to swear off his cannibalism after eating the delicious food she cooks. It’s Grimms’ meets Shrek meets Lolita, a vivid dream that makes crystal-clear emotional sense but on retelling is nonsensical and, frankly, a little troubling.

The title for Zeralda’s Ogre is a hand-painted blackletter that’s equal parts scary and silly. It has a human comfort from being hand-painted, which pulls it clear of looking like the New York Times logo and makes it look more like a backdrop for a high-production-value puppet show.

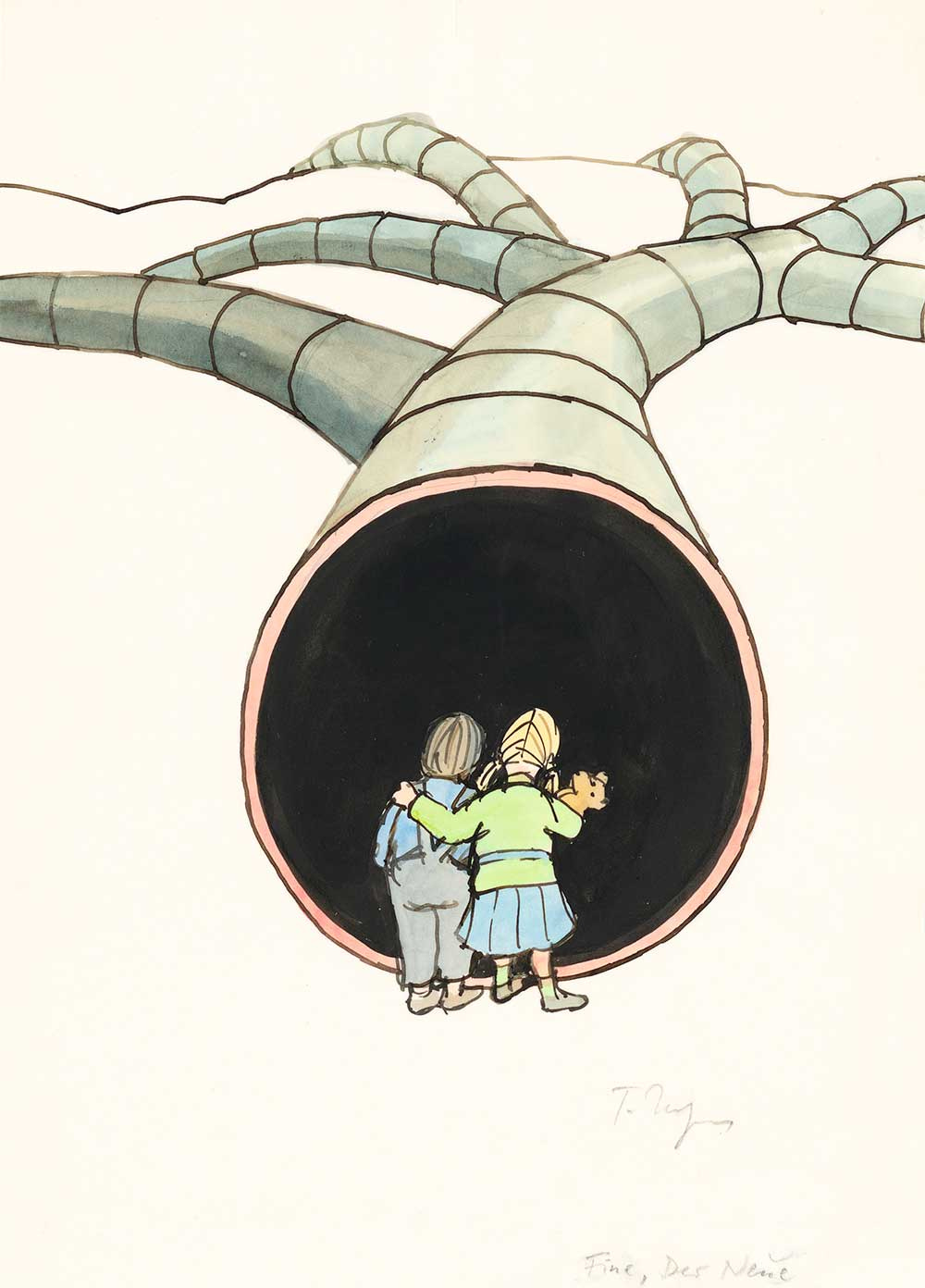

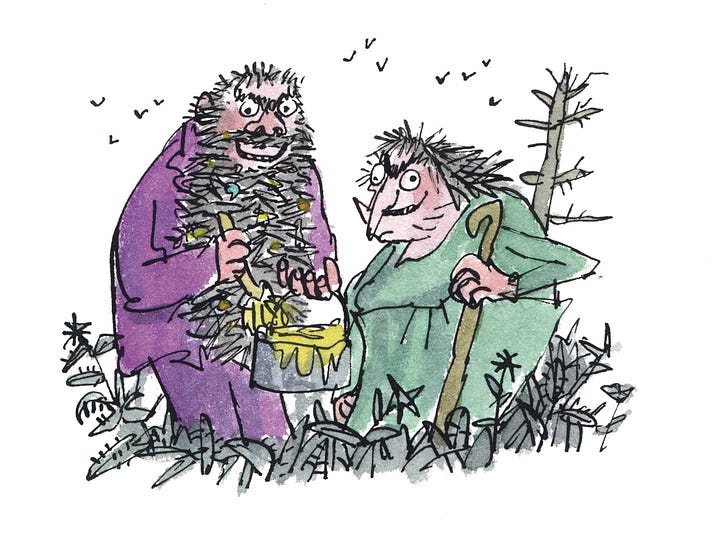

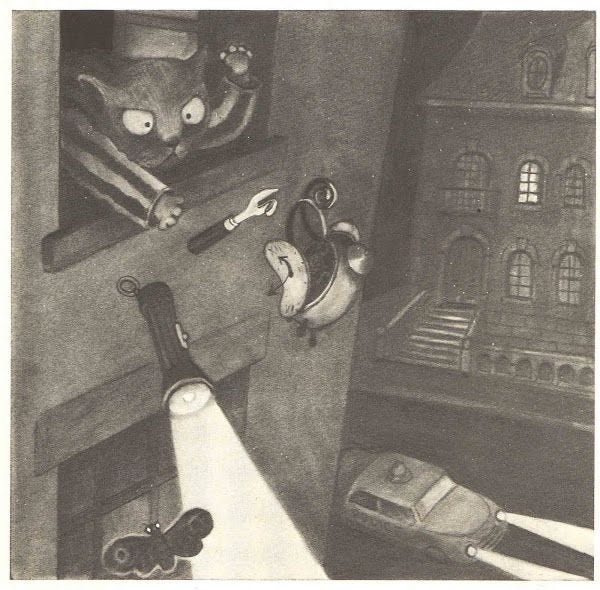

This ominous and fantastical blackletter echoes the impact that illustrators like Tomi, Maurice Sendack, and Roald Dahl had on me as a child. Their books were emotionally ambiguous and without clear morals. Their worlds had legitimate artistic merit: they were personal, fully-rendered places that you wanted to go back to once the book was closed. These worlds had shadows hiding behind corners and children tumbling slowly through the sky and things you couldn’t name if you tried. When you were antsy at a restaurant and were given a cup of crayons to calm down, you could draw extensions of these characters and worlds. Each provided a creative source material, an aesthetic you could pull over your head and run around in.

Outside of these precious few books, the world of children’s media is saccharine, moralistic, glossy, and simple. Most stuff “for kids” bends down at the waist and talks at you in a sing-song voice. It does not give you an opportunity to imagine, let alone a world in which to do it. It asks you what your favorite _______ is, and when it doesn’t get an immediate response it stands up again and goes back to the adults.

Ungerer’s contrasting view of those adults up above (greedy, obscene, self-involved) and children (just, curious, beautiful) feels right, or at least more right than it is wrong. Like many recently-crowned adults, I have the frequent and unfortunate realization that I am, indeed, an adult. And I trust Ungerer because he sat down with me and my cousins at weddings and Thanksgivings and played with us and actually listened to what we said. So when I look at his work now, at my ripe young/old age, I feel a little scared. Am I the pedophilic ogre now, or the wicked robber, or the bankrupt banker? I don’t have the time or spirit to think these thoughts in festive, hand-drawn lettering. They are concerned, 12 point, single-spaced Times New Roman affairs printed in triplicate for diary, friends, and therapist.

After all these years, Tomi’s finally got me scared.